Remembering the

Maestro

50

years ago, Juan Manuel Fangio set the standard for Grand Prix driving

by Steve Barber

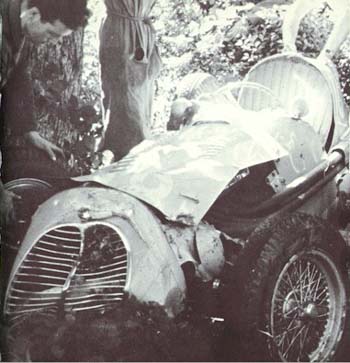

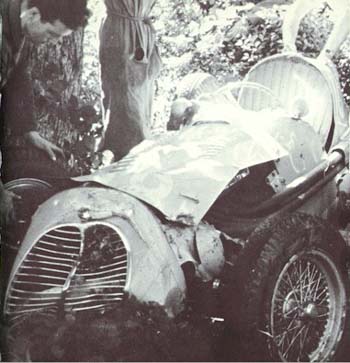

When Fangio lost control

of the Maserati’s slide, the first thought to flash through his mind was

the injustice of it all. After the previous day’s race in Belfast,

he’d missed plane connections in Paris, forcing him to drive all night

here to Monza, arriving only half an hour before the start of the race.

He’d kept his promise to the event organizers to be here. Deeply fatigued,

it seemed only fair that things start going right for him. Instead, the

car’s slide deepened despite his efforts to steer into the skid. Jolting

off the outside edge of the track, the tires lost all traction, and

when they hit the earthen bank beyond, the car became airborne, flipped

end-over-end, then settled in a cloud of ripped turf and dust. Thrown clear,

Fangio

was knocked unconscious and spent the next several hours near death. His

neck had been broken. Fangio

was knocked unconscious and spent the next several hours near death. His

neck had been broken.

Only six months earlier,

Juan Manuel Fangio had been awarded his first Grand Prix world championship.

But he spent the rest of the 1952 season recuperating from this crash,

unable to defend his title. His fans could only wonder: Would he ever race

again? Would he ever drive as well?

For Fangio, accidents were

uncommon. His skills had been honed during 12 years of racing on the unpaved

“killing field” tracks of his native Argentina. His reflexes, sense of

awareness and anticipation were legendary, helping him avoid accidents

which sidelined many others. Often, he declined to even “lift off” in corners

where other drivers felt compelled to brake hard. Above all, he had an

uncanny ability to power-slide his cars through turns.

Stirling Moss, Fangio’s

teammate with Mercedes and Maserati, observed, “The skill that Fangio had

was enormous. What made him great was his concentration and his balance

of the motor car.”

Although always on the edge,

Fangio said after retiring, “I never took an unnecessary risk. I always

knew my limits.”

Auto

Racing’s Grand Master

How good was he? Well, no

driver has ever been more dominant in his generation. When Fangio died

six years ago, the chairman of Ferarri eulogized him as, “the most outstanding

figure in the history of motor racing”. A few years later he was voted

the greatest driver in Formula 1 history. As Uli Wieselmann put it,

“...compared to his capabilities, the entire world elite is thrown into

the second rank.”

Of the 51 Grand Prix races

he entered, he won 24 of them. Not finished, not placed, but won -- and

placed second in 10 others. That’s a record that will likely never be matched.

Besides the highest percentage of wins, Fangio also holds the highest average

of Grand Prix points per race.

Of the eight years

he actively raced in Formula 1, he won the world championship in five of

them, and was runner up in two others. His closest rival in world championships,

Alain Prost, won it four times.

Was Fangio the best because

he always drove the best car? Hardly. He won world championships while

driving for four different marques: Alfa Romeo, Maserati, Mercedes and

Ferrari. In fact, he earned a reputation for his ability to win even while

driving inferior cars, and by driving no faster than absolutely necessary.

Other drivers were often

in awe of Fangio’s skills – referring to him as “the maestro”. John Claes

was one. In practice laps at Spa in 1954, Claes felt that his Maserati

was markedly slower than Fangio’s identical one. So he asked Juan Manuel

to drive it and see. Fangio did, and returned to the pits after turning

several laps at speeds comparable to those in his own car. When Claes asked

him how he did it, Fangio responded humbly in his halting English, “Less

brakes, more accelerator.”

The

Antithesis of a Hero

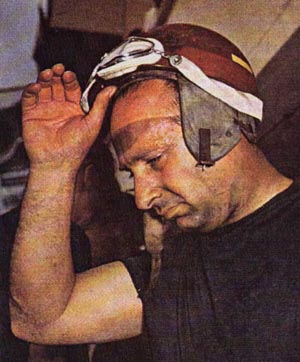

On

first appearance, Fangio was an unlikely racing legend. Short, shy and

balding, he lacked the dashing good looks of contemporaries like Mike Hawthorn

or Alberto Ascari. The son of a decorator, he had a thin, reedy voice and

had even been nicknamed “bandy legs” by his youthful soccer teammates.

When he entered Grand Prix racing at the age of 36, he was considered too

old to compete. While other drivers might act like flamboyant prima-donnas,

Fangio was quiet and gentlemanly. On

first appearance, Fangio was an unlikely racing legend. Short, shy and

balding, he lacked the dashing good looks of contemporaries like Mike Hawthorn

or Alberto Ascari. The son of a decorator, he had a thin, reedy voice and

had even been nicknamed “bandy legs” by his youthful soccer teammates.

When he entered Grand Prix racing at the age of 36, he was considered too

old to compete. While other drivers might act like flamboyant prima-donnas,

Fangio was quiet and gentlemanly.

Fangio’s unassuming nature

was demonstrated in 1950, his first season of Grand Prix racing, when he

was courted by Alfa Romeo to join its team. After driving their new Tipo158

car, he was so eager to race for Alfa that, when their president, Dr. Antonio

Alessio, asked him how much money he wanted, Fangio said simply, “I’ll

just sign the contract and let you fill in the noughts.”

The

Defining Victories

Juan

Manuel Fangio was born in 1911 in Balcarce, Argentina, the son of an Italian

immigrant who made his living as a stonemason, plasterer and painter. During

his teens, Argentina eschewed administrative formalities, Juan

Manuel Fangio was born in 1911 in Balcarce, Argentina, the son of an Italian

immigrant who made his living as a stonemason, plasterer and painter. During

his teens, Argentina eschewed administrative formalities,

so Juan drove for 50 years

before he ever got a driver’s license. At the age of 25, he entered his

first race – in a borrowed Ford taxi – using an alias, “Rivadavia”, so

his parents wouldn’t discover his dangerous new hobby.

Contributions from 250 supportive

citizens of Balcarce enabled him to buy a 1939 Chevrolet coupe. With his

younger brother, Toto, and a bevy of friends helping with modifications,

Juan drove it in several carreteras long-distance races like the Grand

Premio. He finished fifth overall in the 1939 edition, then won it in 1940,

driving his Chevy almost 6,000 miles from Buenos Aires to Lima and back

in two weeks while serving as both driver and mechanic. He was Argentina’s

carreteras champion in 1940 and 1941. The legend had begun. World

War II brought a five-year halt to organized racing. Juan Fangio could

only hope that, when it resumed, he would not be too old to continue his

racing career. Finally, in 1947, at age 35, Fangio returned to racing,

and his exploits drew the attention of Argentina’s new president, Juan

Peron and his actress wife “Evita”, who garnered strong public affection. World

War II brought a five-year halt to organized racing. Juan Fangio could

only hope that, when it resumed, he would not be too old to continue his

racing career. Finally, in 1947, at age 35, Fangio returned to racing,

and his exploits drew the attention of Argentina’s new president, Juan

Peron and his actress wife “Evita”, who garnered strong public affection.

Peron selected him to join

a government-sponsored team to race in Europe during the 1948 season, thereby

supporting the country’s fledgling automobile industry. At last,

Fangio was able to compete on the Grand Prix circuit against the world’s

best drivers. The skill he demonstrated earned the observation that, “...he

has real Grand Prix panache.”

Encouraged

by its success, the team bought two Maseratis to compete in the following

race season. Fangio won the first four Grand Prix races, and a total of

six out of ten in 1949, solidifying his position as a serious contender

for elite Formula 1 driving status. In August, he returned to Argentina

a national hero and was received by Juan Peron at the presidential palace. Encouraged

by its success, the team bought two Maseratis to compete in the following

race season. Fangio won the first four Grand Prix races, and a total of

six out of ten in 1949, solidifying his position as a serious contender

for elite Formula 1 driving status. In August, he returned to Argentina

a national hero and was received by Juan Peron at the presidential palace.

When he had elected to drive

in the 1949 season in Europe, Juan Fangio intended to race there for only

that one year. He knew his age would soon weigh against him. He would return

to Argentina and pursue a choice of lucrative automotive business opportunities.

But after racing that year,

his talent was apparent. He knew it would be wasted if he quit. “I never

dreamed I’d go to Europe and never dreamed I’d be successful”, he said

later. “I knew I would go on racing. It was my life now, and I would go

the whole way, right to the end.”

After 1949, Juan Fangio

would drive only for the Grand Prix teams of the major car manufacturers,

beginning with Alfa Romeo in 1950 when he finished second in the world

championship. The following year he would be first.

Relationships

of a Champion

Because

he’d owned his own garage and maintained his own race cars, Fangio appreciated

the role played by mechanics. Only if his car finished a race could he

hope to win it, so it was logical for him to cultivate the loyalty of his

race team technicians. He did so by promising them ten percent of his winnings.

After breakdowns forced him out of some early Grand Prix races, he always

insisted on being assigned a mechanic dedicated to his car. Because

he’d owned his own garage and maintained his own race cars, Fangio appreciated

the role played by mechanics. Only if his car finished a race could he

hope to win it, so it was logical for him to cultivate the loyalty of his

race team technicians. He did so by promising them ten percent of his winnings.

After breakdowns forced him out of some early Grand Prix races, he always

insisted on being assigned a mechanic dedicated to his car.

His recognition of these

unsung heroes paid off. During practice runs for one race in 1953, his

car developed a severe vibration. But on race day the problem had disappeared.

Secretly, the mechanics had switched cars in the middle of the night, giving

the vibrating one to Fangio’s teammate. Appropriately, five years later,

it was to his mechanic that he said simply, “It is finished.” after settling

for fourth place in the French Grand Prix. And, with that, he retired.

Fangio

returned to Argentina where he served as honorary chairman of Mercedes-Benz

and mentored aspiring race drivers, often appearing at international race

events to acknowledge his adoring fans. Unlike many of his racing contemporaries,

he lived to a ripe, old age, dying in 1995 at the age of 84. A museum in

Balcarce honors his memory today. Fangio

returned to Argentina where he served as honorary chairman of Mercedes-Benz

and mentored aspiring race drivers, often appearing at international race

events to acknowledge his adoring fans. Unlike many of his racing contemporaries,

he lived to a ripe, old age, dying in 1995 at the age of 84. A museum in

Balcarce honors his memory today.

Throughout his career, despite

his lack of movie-star looks, Fangio was considered a lady’s man. According

to fellow racer, Karl Kling, “Fangio loved and treasured women. He was

a charmer. Women fancied him.” While occasionally involved with other

women, he was essentially loyal to one: Andreina “Bebe” Espinosa. Bebe

accompanied him to most Grand Prix events, and he spent 20 years with her

as if they were married.

Who’d

Be The Best?

By today’s standards, the

cars of Fangio’s era had narrow bodies, skinny tires, high roll centers,

no ground effects and few aerodynamic properties. From both a visual and

performance standpoint, today’s Grand Prix cars bear little resemblance

to those of 50 years ago.

So the question arises:

Driving comparable cars, how would Juan Manuel Fangio stack up today against

Grand Prix drivers like Michael Schumacher and Mika Hakkinen? Must we only

speculate? What harm would there be in skewing the time/space continuum

just enough to watch Fangio go head-to-head with them on a challenging

circuit like Silverstone? But, lacking a time machine, all

we can do is wonder and dream. And curse the injustice of it all.

Steve Barber

San Jose, Calfornia USA |

Fangio

was knocked unconscious and spent the next several hours near death. His

neck had been broken.

Fangio

was knocked unconscious and spent the next several hours near death. His

neck had been broken.

On

first appearance, Fangio was an unlikely racing legend. Short, shy and

balding, he lacked the dashing good looks of contemporaries like Mike Hawthorn

or Alberto Ascari. The son of a decorator, he had a thin, reedy voice and

had even been nicknamed “bandy legs” by his youthful soccer teammates.

When he entered Grand Prix racing at the age of 36, he was considered too

old to compete. While other drivers might act like flamboyant prima-donnas,

Fangio was quiet and gentlemanly.

On

first appearance, Fangio was an unlikely racing legend. Short, shy and

balding, he lacked the dashing good looks of contemporaries like Mike Hawthorn

or Alberto Ascari. The son of a decorator, he had a thin, reedy voice and

had even been nicknamed “bandy legs” by his youthful soccer teammates.

When he entered Grand Prix racing at the age of 36, he was considered too

old to compete. While other drivers might act like flamboyant prima-donnas,

Fangio was quiet and gentlemanly.

Juan

Manuel Fangio was born in 1911 in Balcarce, Argentina, the son of an Italian

immigrant who made his living as a stonemason, plasterer and painter. During

his teens, Argentina eschewed administrative formalities,

Juan

Manuel Fangio was born in 1911 in Balcarce, Argentina, the son of an Italian

immigrant who made his living as a stonemason, plasterer and painter. During

his teens, Argentina eschewed administrative formalities,

World

War II brought a five-year halt to organized racing. Juan Fangio could

only hope that, when it resumed, he would not be too old to continue his

racing career. Finally, in 1947, at age 35, Fangio returned to racing,

and his exploits drew the attention of Argentina’s new president, Juan

Peron and his actress wife “Evita”, who garnered strong public affection.

World

War II brought a five-year halt to organized racing. Juan Fangio could

only hope that, when it resumed, he would not be too old to continue his

racing career. Finally, in 1947, at age 35, Fangio returned to racing,

and his exploits drew the attention of Argentina’s new president, Juan

Peron and his actress wife “Evita”, who garnered strong public affection.

Encouraged

by its success, the team bought two Maseratis to compete in the following

race season. Fangio won the first four Grand Prix races, and a total of

six out of ten in 1949, solidifying his position as a serious contender

for elite Formula 1 driving status. In August, he returned to Argentina

a national hero and was received by Juan Peron at the presidential palace.

Encouraged

by its success, the team bought two Maseratis to compete in the following

race season. Fangio won the first four Grand Prix races, and a total of

six out of ten in 1949, solidifying his position as a serious contender

for elite Formula 1 driving status. In August, he returned to Argentina

a national hero and was received by Juan Peron at the presidential palace.

Because

he’d owned his own garage and maintained his own race cars, Fangio appreciated

the role played by mechanics. Only if his car finished a race could he

hope to win it, so it was logical for him to cultivate the loyalty of his

race team technicians. He did so by promising them ten percent of his winnings.

After breakdowns forced him out of some early Grand Prix races, he always

insisted on being assigned a mechanic dedicated to his car.

Because

he’d owned his own garage and maintained his own race cars, Fangio appreciated

the role played by mechanics. Only if his car finished a race could he

hope to win it, so it was logical for him to cultivate the loyalty of his

race team technicians. He did so by promising them ten percent of his winnings.

After breakdowns forced him out of some early Grand Prix races, he always

insisted on being assigned a mechanic dedicated to his car.

Fangio

returned to Argentina where he served as honorary chairman of Mercedes-Benz

and mentored aspiring race drivers, often appearing at international race

events to acknowledge his adoring fans. Unlike many of his racing contemporaries,

he lived to a ripe, old age, dying in 1995 at the age of 84. A museum in

Balcarce honors his memory today.

Fangio

returned to Argentina where he served as honorary chairman of Mercedes-Benz

and mentored aspiring race drivers, often appearing at international race

events to acknowledge his adoring fans. Unlike many of his racing contemporaries,

he lived to a ripe, old age, dying in 1995 at the age of 84. A museum in

Balcarce honors his memory today.